My Senior Capstone project, Reservoir, is the largest, most complex single artwork that I have created to date. It is an interactive fountain that I designed and built between May 2022 and April 2023. By using a series of tactile interactive elements to create an emulation of a natural hydrological system, the project seeks to make a commentary on the way humans collaboratively use and abuse natural resources.

Below you will find media from the 2023 NYUAD Interactive Media Capstone Festival featuring reservoir, as well as an essay about the project and links to my blog documenting the process.

Below is an essay I wrote explaining the project and my making process.

Introduction

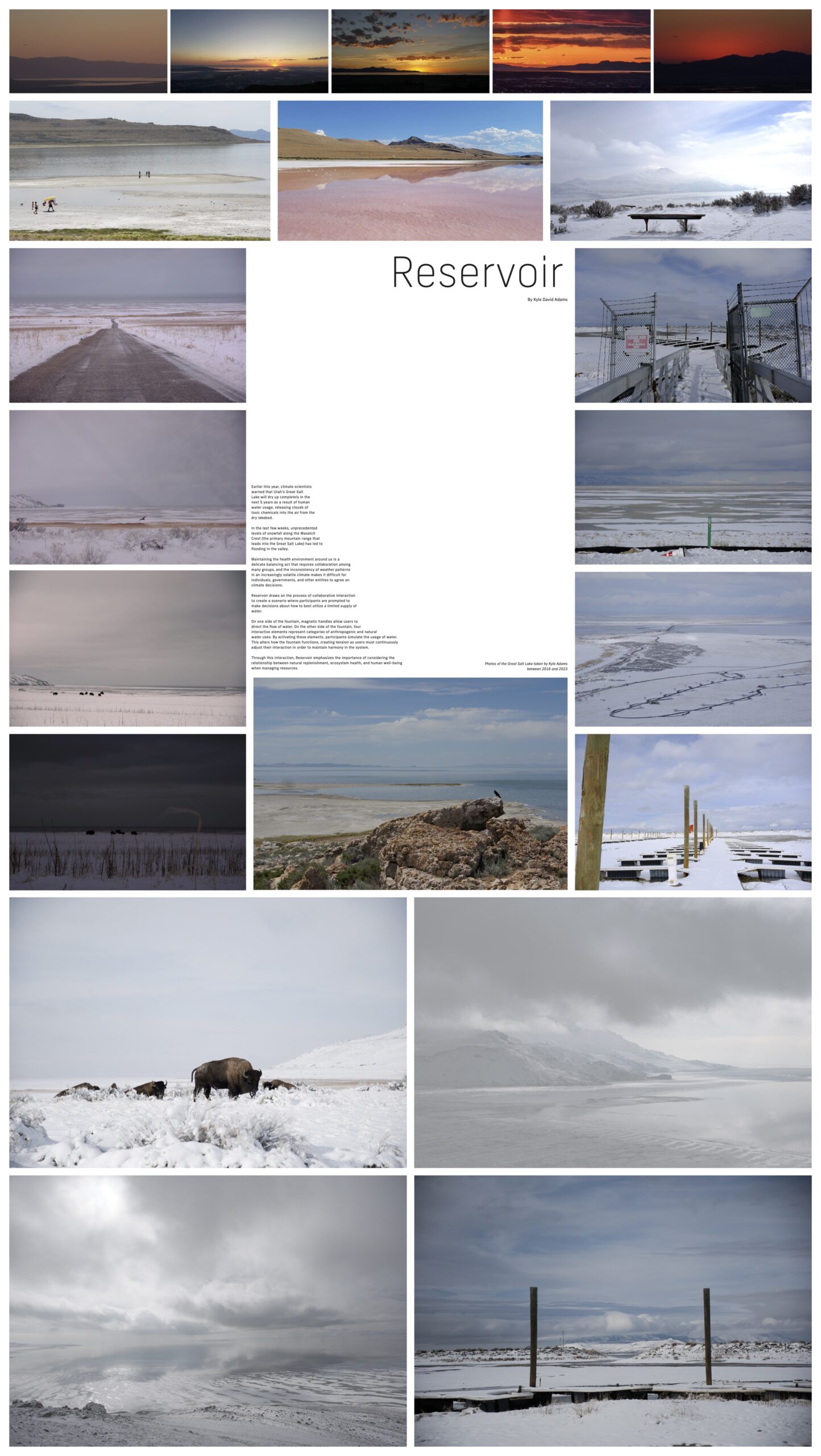

At the beginning of 2023, climate scientists warned that Utah’s Great Salt Lake could dry up completely within the next 5 years as a result of human water usage, releasing clouds of toxic chemicals into the air from the dry lakebed. This dire prediction created a groundswell of support for water conservation and calls for political change. Ironically, in the months leading to my capstone exhibition, unprecedented levels of snowfall along the Wasatch Mountains (the mountain range that provides most of the water that flows into the Great Salt Lake) has led to flooding in the valley. The hydrological system of the Great Basin Desert and its surrounding areas is delicate and dynamic. The introduction of agriculture, industry, and urbanization disrupts the area’s natural balance. Climate change and the expanding urban footprint have considerably exacerbated this problem. I would suggest that in order to maintain the highest standard of living for the people living in America’s desert west, as well as the health of the environment, many anthropogenic and natural factors must work in harmony. Uncertainty, miscommunication, and a lack of community climate awareness leads to the breakdown of effective policy decisions about how to mediate the climate crisis. Through this capstone project, I hope to increase awareness of the strain that an increasingly volatile climate puts on delicate natural processes when individuals, governments, and other entities struggle to agree on climate decisions. I have done this by showing how both harmony and disharmony in the process impact climate outcomes.

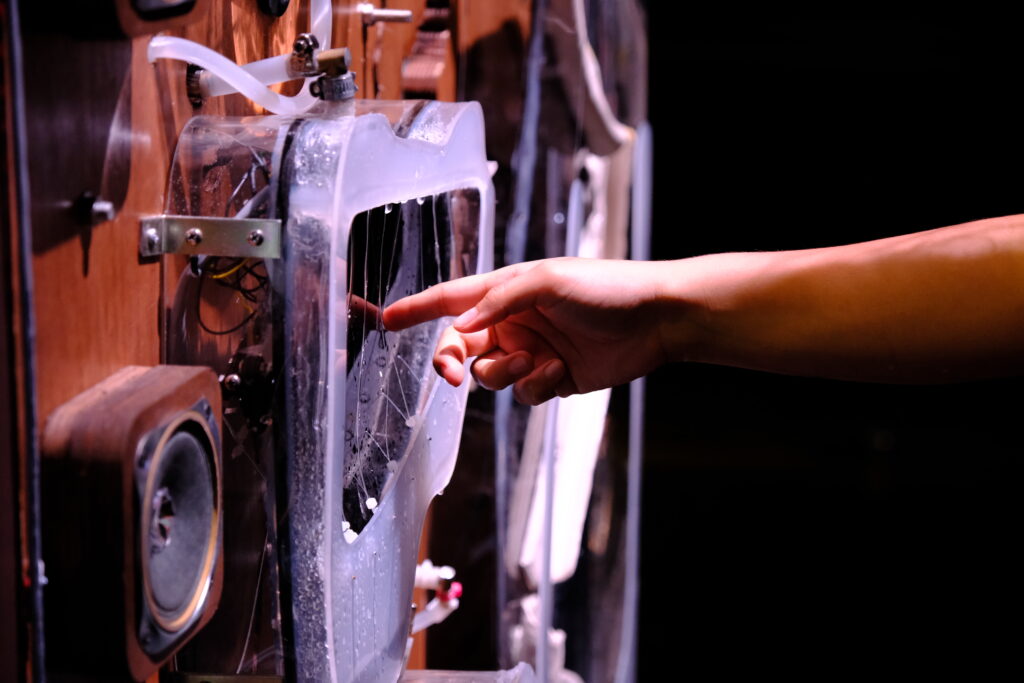

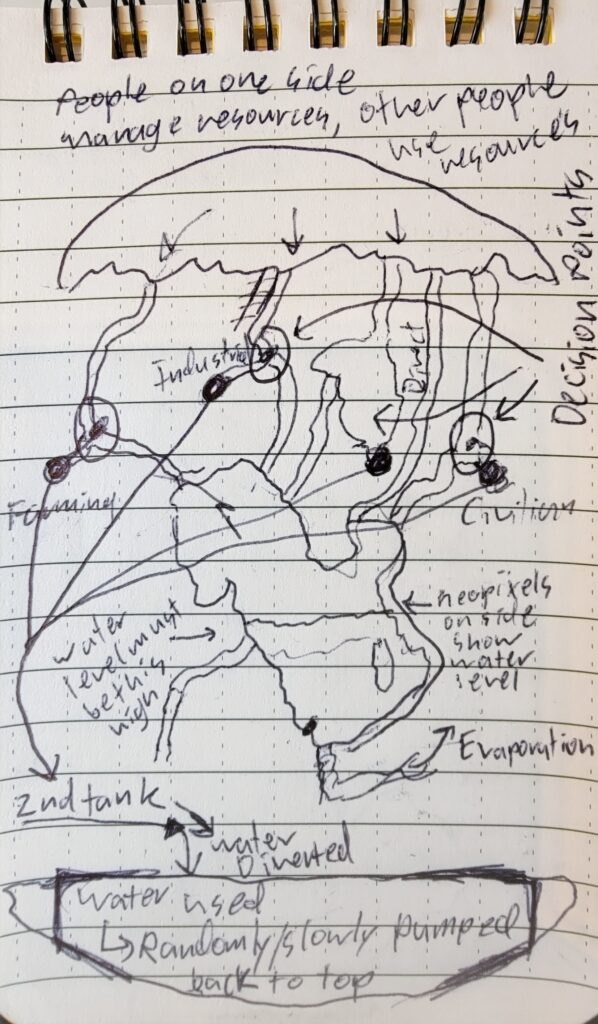

My capstone installation, Reservoir, draws on the process of collaborative interaction to create a scenario where participants are prompted to make decisions about how to utilize a limited supply of water. Water not only drives the concept that inspired Reservoir; it is also the medium used to create the interaction itself. On one side of the fountain, magnetic handles allow users to direct the flow of water. On the other side of the fountain, four interactive elements represent categories of anthropogenic and natural water uses. By activating these elements, participants simulate the usage of water. This in turn alters how the system functions. There is enough water being channeled through the system to activate every part of the fountain, yet small inconsistencies and inefficiencies make it difficult to maintain this balance when users interact with it. Several physical properties of the sculpture, which I will describe in detail later, create a mechanical circuit in which the flow of water plays a similar role to electricity in an electrical circuit. Reservoir responds to user input through several methods, each with different temporal qualities. The atmosphere around the piece is created by immediate stimulus responses in the form of auditory, visual, and tactile feedback. Over time, however, the accumulation of user inputs slowly changes how these stimuli respond to user input. This secondary interaction is not on a scale that any single user can perceive unless they spend a significant amount of time understanding the way minute details change over time. As we see in nature, every interaction has cascading effects within the system. Through the feedback cycle created by this system in response to user input, Reservoir makes the argument that it is the lack of communication and cumulative understanding about humanity’s place in maintaining natural systems, not the inherent use of resources, that leads to the degradation of the environment. In this, Reservoir emphasizes the importance of considering the relationship between natural replenishment, ecosystem health, and human well-being when managing resources.

The two sides of Reservoir: On the left the blue outline of the Great Salt Lake contrasts with the brown outlines of the watersheds that supply the lake. Magnetic handles allow for users to direct water flowing from the mountains at the top of the piece into either the lake or the cups that supply the other side with water. On the right, interactive modules are altered by changes in the water’s flow. Sound is triggered both by this water and by the user.

Research Process

My capstone project started as an amorphous idea about education and tactile interactivity and developed into the complex and nuanced interactive installation it is today. In order to develop the theoretical basis for my project in context with other interactive media artists, I have looked towards activists such as Julian Oliver, who creates critical artworks that offer commentaries on subjects such as digital privacy and environmental activism. Oliver is a champion of art as protest and has made works that, like mine, discuss culturally relevant concepts via the procedural form within an artwork.

As an initial research outline, I created a rough list of goals that represented the technical and conceptual elements that I wanted to explore through my capstone process:

- I wanted to make something physically large and technically complicated that would allow me to explore various mediums and learn new skills

- I wanted to make something that used art and interaction in order to inspire/encourage people to think critically about the world around them.

- I wanted to create something that used tactile feedback to facilitate interaction in a meaningful way

- I wanted to create an art piece that had different levels of interaction — ie. a child could find playful joy in the piece, that interaction is connected to something deeper, and interaction with the art piece serves to positively inform and reshape our perspective.

These constraints conclusively allowed me to develop a research ethos that superseded the ultimate form and concept of my capstone project. Using tools I learned through my experience as an interactive media student, I began to explore innovative ways to address the intersection of conservation, activism, and education. Through my research process, I ultimately found myself centered upon the goal of nudging users to consider the nuances of water usage. I wanted to create a space where users are inspired to think critically about resource allocation. Thus, very early in my ideation process, I decided to focus on exploring both the physical and cultural properties of water as the key element of this project. With a well scrutinized framework in place, I began to make connections between my technical goals and what I found conceptually meaningful.

Additionally, during my junior spring at NYUAD, I took a core class called “Desert” in which we explored the sociocultural significance of desert spaces around the world. As a result of my research in this class, I began to reconnect with the story of my home desert, rediscovering Artists such as Katie Lee and Edward Abbey. Further, while ideating my capstone, I began examining how they channeled their activism through their art. Lee was an author, actor, and folk musician born in 1919. In response to the planned construction of the Glen Canyon Dam, she ran the Colorado river with her friends Frank Wright and Tad Nichols from 1954 to 1963, exploring and experiencing as much of it as they could before the canyon’s time ran out.

Glen Canyon, now Lake Powell, was my initial focus when Ideating this project. Like the Great Salt Lake, Lake Powell is a natural space that has been catastrophically altered by bureaucratic decisions regarding how to extract the most immediate economic benefit from water. In other words, I began to see the drying of the Great Salt Lake as a modern parallel to the damming of Glen Canyon. In respect to this historical parallel, I hope my work will serve as an interactive record and calling card in the way Lee’s Folk Songs of the Colorado River or Abbey’s Desert Solitaire archived their own moment in the American West.

In order to jumpstart my own research, I took my own series of journeys to the Great Salt Lake. I was inspired by Lee and Abbey, who collectively spent decades exploring the deserts of southern Utah. Over the last several years and during every season, I have taken trips to the Great Salt Lake, exploring from the rocky plains of Antelope and Stansbury Islands to the wetlands along the Jordan and Bear Rivers which are the major tributaries of the lake. In the course of my experiences hiking, photographing, and exploring, I spent time developing a deeper understanding and appreciation of the Great Salt Lake. A photographic record of my experiences showcasing my desire to form a deep understanding of the Great Salt Lake is showcased in my final installation to provide supplemental information next to the fountain.

As I connected the words of Edward Abbey and Katie Lee and the parallels I make, I considered Lee’s own activism. After the damming of Glen Canyon, Lee spent the next 55 years of her life advocating awareness of environmental issues around the Southwest. Lee’s observations empowered me to ask the question, “how can I facilitate (at least in some part) an experience that educates or inspires people to care about the environment?” Although I share many of the feelings of loss and frustration that Abbey and Lee expressed in their works, I do not specialize in literary art forms that allow for the direct sharing of complex theoretical discussions and narratives. Interactive media, however, has the potential to enable even more nuanced and meaningful expressions of activism than written word by placing the actual viewer in a position where they see how they affect the world around them.

The earliest iteration of this project was my idea to use ceramics in capacitive sensing. My theory was that by introducing water to ceramic tiles, a material traditionally used for its insulating properties, I could make them conductive. I speculated that if this was successful, I could use the tiles to trigger different events using capacitive sensing. Consequently, I spent the summer experimenting with this idea and researching the technologies that could help me create these objects. Although I made some interesting discoveries, I struggled to justify using ceramic tiles and water in the context of my theoretical motivations. In response, I began expanding the technical idea of capacitive sensing into a larger project by considering these various technologies as nodes in part of a larger system. As I developed my idea, I discovered that the way I planned to process matter and energy began to resemble a cybernetic system. Considering my project from this perspective I realized that my artwork would effectively be a homeostat machine, like the one originally created by William Ross Ashby in the late 1950s. In order to justify this concept further within the field of interactive media artworks and to understand how the concept of homeostasis had previously been used in interactive artworks, I found inspiration in the works of Luke Blackstone, who creates artworks that use a combination of homeostatic equilibrium and human-made or nature-made disruptions to represent systems outside the artwork, in turn making a commentary on. Blackstone’s sculptures, such “Homeostasis” (2017) and “Tacoma Preservatory of Fluid Moment” (2001) are great examples of how cyclical systems, balance, and environment can be used in order to create compelling pieces of public art that are beautiful in their own right, but have a meaning that transcends their aesthetics.

Consequently, I revisited the works of early environmental activists of the American southwest when considering the design and application of the concepts I wanted to explore in my project. John Wesley Powell (who Lake Powell was ironically named after) wrote a series of essays between 1899 and 1901 that approached conversations about natural spaces through the lens of “design without designers.” The concept of design without designers, which is discussed in Keith M. Murphy article, Design and Anthropology proposes that the physical qualities of geological, hydrological, and climate systems shape the natural world. Powell further suggests that the “natural design” found in the inherent physical properties of natural spaces and systems leads people to interact with them in certain ways. When designing my first homeostat machine I took this into consideration, with the goal of replacing this natural design with my own design, inspired by the original natural system. This conceptual prototype took the form of a massive interactive installation centered around a large transparent ring that would distribute water to various panels with interactive elements.

The image to the left is one of my early renderings of “The Ring.” People would interact with the purple panels. Each panel would use a different type of interaction to represent a different type of water usage, a concept that was carried on into the final piece.

The ring would tilt to either restrict or enable the flow of water into various sections based on how users interacted with the panels themselves. This machine would treat interaction and output as limited resources, tilting the ring slowly away from panels as resources were used up. This iteration was inspired by Newton’s Daydream, a two story tall interactive sculpture installed in the Clark Planetarium in Salt Lake City, Utah. The work, designed and fabricated by George Rhoads is effectively a large, incredibly intricate marble track that carries balls of two different sizes from ground level to the top of the machine where a variety of tracks and devices guide them down again as they interact with different parts of the machine. These tracks can be controlled via knobs and sliders on both the upper and lower levels of the machine, allowing the user to control where the balls go and create a sort of butterfly effect within the system. The cyclical nature of this piece is what will be most similar to my artwork, which instead of using balls, will use water as its focus of interaction and movement.

Although I found this design quite compelling, several factors began pushing me in slightly different directions. Budget and time constraints were looming and the logistics of hanging heavy water-filled objects above people’s heads in a gallery setting were daunting. These were the main factors that directed me to readjust my vision and scale back. I also felt like this would allow me more space to perfect the system. This led me to plan the creation of an interactive fountain that takes the form of a single wall accessible from both sides. At this point in my research process, I found that the only way to move forward was to start building prototypes in order to see how I could feasibly create a physical object that could communicate my message.

Technical Research

The nature of my project led me to spend the majority of my time designing a form that would be conducive to the story of water’s impact on its environment I was trying to tell. Having worked on large physical installations before, I anticipated the plethora of challenges and setbacks I would face. For this reason I made an effort to work on my design a month or two ahead of the regular capstone schedule, leading me to complete my first major prototype by the end of fall semester. Working ahead of schedule was fortuitous; I was able to learn exactly which areas of the project were physically possible to create with the resources I had available. I was also able to see which aspects connected with my audience and which did not. Additionally, the feedback from my final fall semester presentation was incredibly valuable in helping me to identify two major problems with my project up to that point:

- Any problems with leaking or dysfunctional parts of the fountain would be distracting unless they were an explicit and intentional part of the experience.

- I needed to solidify my concept and communicate it visually, as well as through how I designed the interaction.

I began winter break with tentative plans to redesign the project. My user feedback and the technical discoveries I made over the course of my initial prototyping process each played major roles in how I decided to move forward with the project. My modus operandi became “simplification.” I struggled to tell a compelling story about water and resources. My solution was to tell a simpler story about a specific issue that represented that larger issue. Too many moving parts in one of my designs made the prototype run inconsistently. My solution was to figure out a way to do the same things with fewer moving parts. Having many panels made water sealing a nightmare and prevented me from scaling up due to budget constraints. My solution was to encapsulate the entire main body of the fountain in a single large panel which I could meticulously seal. These decisions ultimately lead to the creation of Reservoir’s final design, the two sided fountain with the Great Salt Lake concept at the center.

The refinement of this design pushed me to look at the construction of my projects in new ways. For example, I had previously planned to cut most of my fountain components with a laser cutter, but the way I planned to scale up meant I had to cut much larger sheets of materials, leading me to learn CNC machining. Similarly, I had to learn how to weld in order to create a frame sturdy enough to safely support my large installation. Designing and redesigning the main part of the fountain in response to new knowledge and feedback from my peers and instructors took several months. Much of my time was spent on Adobe Illustrator, carefully planning how water would flow through the piece. During this time I took breaks to construct and test the interactive modules. They not only needed to be leak proof, but also interact safely with my electronics. Similarly, I began testing different methods of directing the water as well as sensing where in the system the water was at any moment, which I planned to use in order to change the feedback that the fountain provided. I tested various float sensors as well as electrodes that sensed moisture, but became worried about the continuous functionality of the sensors since they would need to be sealed into the fountain. Eventually I settled on using a water flow sensor in order to detect the pressure coming out of the lake itself. This gave me a value that accurately let me assess the level of the lake in the fountain.

After my initial CNC Session, I was finally able to do user testing at scale. Seeing it visually come together was fantastic but the model had several significant problems. The magnets I used fell out of their acrylic housing inside the fountain and began to rust. Even before this they were difficult to move. I solved this later by investing in much larger and more expensive epoxy-coated magnets that greatly helped these issues. Another problem that the scale testing presented was deterioration of the acrylic and fittings I used. When water was added to the fountain, the thin acrylic I had used as the inner and outer walls began to flex and deform, squeezing the magnets and causing problems with how the water flowed. I fixed this by re-cutting these pieces with my last two panels of thicker acrylic, which thankfully fixed the problem. The fittings I used at this point were made of plastic which I had to cut by hand in order to fit it between the fountain’s layers. These warped over time, causing leaks. The small outlet of these fittings also prevented water from being directed into the modules. I solved both of these problems by custom manufacturing brass fittings with larger outlets. My final round of user testing focused on developing and refining the aesthetics of the piece. Up until this point, The fountain was made of raw lightly colored plywood. Taking the advice of several users who had struggled to identify what the shape in the middle of the fountain was, I decided to highlight the lake in blue to make the lake stand out as a central element. I chose the other colors in order to make the piece cohesive with the steel frame.

Fountain functionality

During installation, I was finally able to see each of the elements of the piece come together. Reservoir is roughly 8 feet tall and four feet wide, made of plastic, wood, and steel. A large platform hides the 15 gallon tank and pump that supply it with water under the side of the fountain where users interact with the water. The electronics that run the fountain are hidden on the other side in order to minimize the potential for water to get in and ruin them. Four tiny 4.1 microcontrollers take input from the modules and output stereo audio into speakers on each side of the modules. I spent quite a bit of time preparing the modules and working out the details of the audio feedback, but a series of logistical issues made it so that installation was the first time I was able to hear all of the interactive modules together. My sound designer, Mary Collins, created a custom soundscape that would mix differently depending on which modules were functioning. These sounds were designed in order to portray aspects of the different types of types of water usage each module represented. To our delight the sounds mixed beautifully, just how we imagined them.

I initially planned for users to see the impact of their decisions in real time. Over time I found myself moved more by the idea that the outcomes of our actions and interactions are not immediately perceptible. For this reason, I adjusted the project so it had multiple layers of user feedback. Some types of feedback, like the triggering of a module’s sound, were immediately evident, while other changes in the system played out over time. This felt like it better emulated the way the system I was portraying functions in reality.

The physical properties of water play a significant role in the way each part of the work functions. I was able to design the fountain to use these properties through extensive testing and ideation. Surface tension causes the water to cling to the acrylic on the inside of the fountain, allowing users to clearly see defined streams of water. This also makes it so that even small changes in input can lead to drastic changes in the actual flow of water. When the fountain sits idle, the streams form desire-paths along the surface of the acrylic. Upon being touched by the magnets, the streams will make an attempt to wrap around the object and maintain its original course. For this reason it can take a significant amount of fiddling to truly alter the flow. Surface tension also plays a major role in the functionality of the modules. The civilian module, or orb, allows users to touch the water as it cascades over an acrylic orb. On the industrial module, fishing line guides the flow of water into a basin, hiding the strings in an optical illusion when the flow is just right. Both the agriculture and nature modules use surface tension and capillary action in order to change the sensitivity and activation of their respective capacitive inputs. Because the modules are open to the air, more water is lost from the system when people interact with it. This is one analogy for the cost of human influence within the piece. The flow of water also creates two distinct types of sound on its own within the piece. In addition to the sound of dripping and sloshing caused by the interaction between water and the fountain’s structure, the capacitive elements in the modules can be triggered by the flow of water itself. This creates rhythms that seem to form of their own accord.

Reflection

Although I consider this project a major success, there are several aspects of the piece that I would change and explore in further iterations. Understandably, many of these problems only came to light when I was able to observe large groups of people interacting with the piece. The massive amount of construction and design this artwork required meant that I was only able to do comprehensive user testing at the very tail end of the capstone process. Luckily the significant amount of modular testing I had performed prior to the project’s completion allowed me to create a cohesive work that functioned mostly as desired. In fact, the system I created began to demonstrate traits that made sense in the context of the piece, even though I hadn’t explicitly planned them. Some examples of this are a suction sound that is created only when the water in the basin of the civilian module reaches a certain mass, or the way the Agriculture module becomes overloaded when too much water is applied over the course of several hours.

As the creator of this project, it is difficult to reconcile my complex ideas about the work with what people actually experience. The feedback I have received has been incredibly varied. Some visitors expressed hesitation at the idea of even touching the piece. Others have given up at various points of interaction because the way the magnets moved was not obvious. The feedback that makes me feel the most validated has been from visitors who choose to spend an extended period of time with the piece, carefully discovering how each part works. Overall, I am satisfied with the feedback, although it has prompted me to reconsider certain aspects of how the piece is presented. Most of these changes would serve to make it more immediately accessible and inviting to more people. However, I am conflicted about this as this metric of accessibility demonstrates a key element of the piece: the idea that the discourse and understanding of water rights and resource allocation is messy, inconsistent, and unclear. With that in mind, I am almost completely satisfied with the artwork as it is now.

Still, there are aspects of the project that I still would like to change, update, or upgrade. First of all, I would like to spend a significant amount of time testing the various components so that I can have more control over what happens in response to different interactions. During my final coding process I was forced to cut some interactions, such as the digital change in audio in response to the lake’s level, because I was unable to get them working reliably in time. I understand now that this didn’t have a major impact on the final outcome because the average user is overwhelmed as is, but it was something that I faced anxiety over. Most of my major struggles with this project were a result of the serious budget and time constraints I had to work under. The visual outcome of the piece was satisfactory, but in my opinion lacks some refinement, especially on the side with the modules. If I were to get a grant to put this in a museum, for example, I would commission or engineer more refined custom fittings to improve the durability and aesthetics of the piping.

Technically, Reservoir is a project with many moving parts, each of which I could take out of the project and make/justify its own piece. This gives me hope that even if this piece in its current iteration isn’t displayed again, I will be able to take what I learned from the construction and testing of these various pieces into new projects in the future. Reservoir uses technology and design to convey a message through art. For this reason I believe that my project embodies the spirit of interactive media. I have spent my time and resources creating an interesting and unique framework that has an incredible amount of potential for further research. With more time to implement and test the piece, I believe I could make it into something truly special. With this in mind, my next step is to take the incredible documentation I gathered at the Interactive Media showcase and create a custom website for the project. I plan to make pages describing each part of the fountain in detail with the idea of marketing each module as the potential basis for its own interactive installation.

Bibliography

Abbey, Edward. The Monkey Wrench Gang. Dream Garden Press, 1985

Abbey, Edward. Desert Solitaire: A season in the Wilderness. Simon & Schuster. 1968.

Ashby, William Ross. “The Homeostat.” Design for a Brain: The Origin of Adaptive Behaviour /, Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht , Berlin, Germany, 1972, pp. 100–121.

Axel, Nick et al. Accumulation : The Art, Architecture, and Media of Climate Change, University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

Blackstone, Luke. Luke Blackstone Home Page, 2022, http://www.lukeblackstone.com/.

Carter Williams, KSL.com Updated – April 4. “Utah’s Snowpack Breaks 71-Year-Old Record; Cox Issues Flood Declaration as Melt Nears.” KSL.com, April 4, 2023. https://www.ksl.com/article/50614041/utahs-snowpack-breaks-71-year-old-record-cox-issues-flood-declaration-as-melt-nears?fbclid=IwAR09pbJHDBtjbNfrNPoCOz2edEMzkSZCNFKsAVG90st6HvaOxZUYiGrZ46w.

Creative Machines Inc. Creative Machines, 2022, https://www.creativemachines.com/.

Demos, T. J.. Beyond the World’s End : Arts of Living at the Crossing, Duke University Press, 2020, pp, 177

Flavelle, Christopher, and Bryan Tarnowski. “As the Great Salt Lake Dries up, Utah Faces an ‘Environmental Nuclear Bomb’.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 7, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/07/climate/salt-lake-city-climate-disaster.html.

George, Rhoads. George Rhoads, 2022, http://georgerhoads.com/.

Hanska, Cannupa. Cannupa Hanska, http://www.cannupahanska.com/.

Kostelanetz, Richard. A Dictionary of the American Avant-Gardes, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019.

Murphy, Keith M. Design and Anthropology, Annual Review of Anthropology 45, no. 1, 2016, pp, 433–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-100224.

Oliver, Julian, et al. The Critical Engineering Manifesto, 2011, https://criticalengineering.org/.

Oliver, Julian. “Julian Oliver.” Julian Oliver/, 2022, https://julianoliver.com/.

POWELL, J. W. “Esthetology, or the Science of Activities Designed to Give Pleasure.” American Anthropologist 1, no. 1 (1899): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1899.1.1.02a00020.

POWELL, J. W. “Philology, or the Science of Activities Designed for Expression.” American Anthropologist 2, no. 4 (1900): 603–37. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1900.2.4.02a00020.

POWELL, J. W. “Sophiology, or the Science of Activities Designed to Give Instruction.” American Anthropologist 3, no. 1 (1901): 51–79. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1901.3.1.02a00050.

Schudel, Matt. “George Rhoads, Creator of Whimsical ‘ball Machine’ Sculptures, Dies at 95: His Audiokinetic Sculptures were a Combination of Engineering, Artistry and Humor.” The Washington Post, Aug 01, 2021.

Uwe Seifert, et al. Paradoxes of Interactivity : Perspectives for Media Theory, Human-Computer Interaction, and Artistic Investigations. Transcript Verlag, 2008.

Wiener, Norbert. Cybernetics: Second Edition. MIT Press, 1961.

Weir, Bill. “Scientists Fear a Great Toxic Dustbowl Could Soon Emerge from the Great Salt Lake.” CNN. Cable News Network, February 10, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/10/us/utah-great-salt-lake-dust-pollution-weir-wxc.

![[object Object]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwp.kyleadams.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2Flouvre-e1734549734229.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)

![[object Object]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwp.kyleadams.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2Fmary-video-cover-e1734549892891.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)